Evolutionary determinants of morphological polymorphism in colonial animals

Simpson, C., Jackson, J. B. C., Herrera-Cubilla, A. 2017. Evolutionary determinants of morphological polymorphism in colonial animals. American Naturalist. 190(1): 17-28. link

Preprint version available at bioRxiv doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/046409 pdf

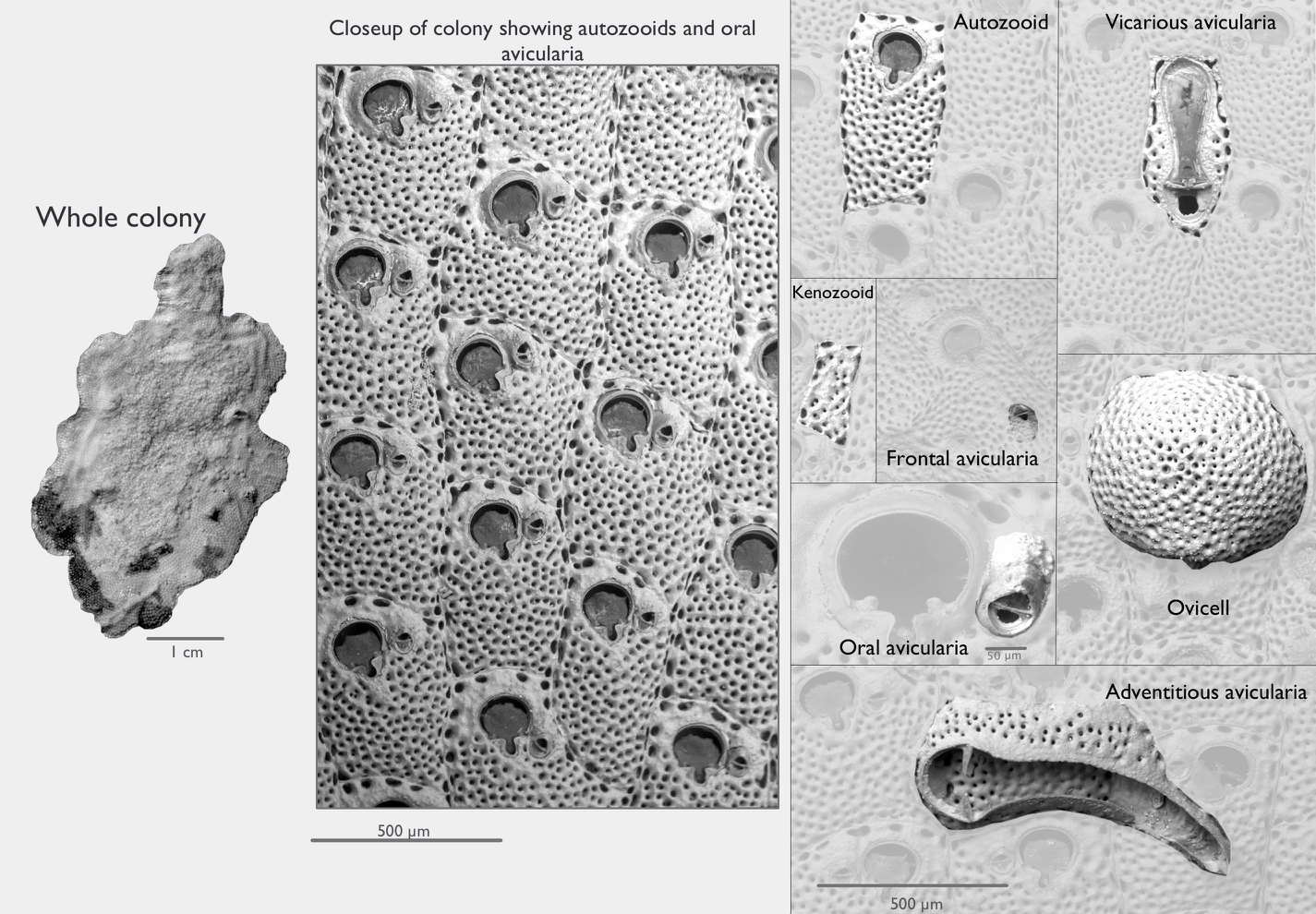

Colonial animals commonly exhibit morphologically polymorphic modular units that are phenotypically distinct and specialize in specific functional tasks. But how and why these polymorphic modules have evolved is poorly understood. Across colonial invertebrates there is wide variation in the degree of polymorphism from none in colonial ascidians, to extreme polymorphism in siphonophores such as the Portuguese Man of War. Bryozoa are a phylum of exclusively colonial invertebrates that uniquely exhibit almost the entire range of polymorphism from monomorphic species to others that rival siphonophores in their polymorphic complexity. Previous approaches to understanding the evolution of polymorphism have been based upon analyses of (1) the functional role of polymorphs or (2) presumed evolutionary costs and benefits based upon ergonomic theory that postulates polymorphism should only be evolutionarily sustainable in more “stable” environments because polymorphism commonly leads to the loss of feeding and sexual competence. Here we use bryozoans from opposite shores of the Isthmus of Panama to revisit the ergonomic hypothesis by comparison of faunas from distinct oceanographic provinces and we then examine the correlations between the extent of polymorphism in relation to patterns of ecological succession and variation in life histories. We find no support for the ergonomic hypothesis. Distributions of the incidence of polymorphism in the oceanographically unstable Eastern Pacific are indistinguishable from those in the more stable Caribbean. In contrast, the temporal position of species in a successional sequence is collinear with the degree of polymorphism because species with fewer types of polymorphs are competitively replaced by species with higher numbers of polymorphs on the same substrata. Competitively dominant species also exhibit patterns of growth that increase their competitive ability. The association between degrees of polymorphism and variations in life histories is fundamental to understanding of the macroevolution of polymorphism.